Enheduanna, a Sumerian priestess, one of the earliest women known by name through archaeology, who lived in the 23rd century BC in ancient Mesopotamia, is considered to be the first poet and named author of either gender. Although there were several previous instances of poems and stories written down, she was the first to sign a name to her work, which influenced hymns for centuries. She was a daughter of Sargon of Akkad, the founder of the Akkadian Empire, the first great empire of the world, when the northern and southern Mesopotamia was united for the first time in history and the city of Akkad became one of the largest in the world. After having conquered Ur, Sargon wanted to consolidate the Akkadian dynasty's links with the traditional Sumerian past in the important cult and political centre of Ur and appointed Enheduanna as the high priestess of the most important temple in Sumer, the temple of the moon deity Nanna-Suen in Ur (in modern-day Southern Iraq), with the responsibility to meld the Sumerian gods with the Akkadian ones, for the much needed stability of his empire. Nanna-Suen was a Sumerian deity in the Mesopotamian mythology of Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia. A traditional divine marriage ceremony was celebrated to make Enheduanna the wife of Nanna, the physical manifestation of the goddess on earth. The celestial nature of her occupation is reflected in her name, which means Ornament of Heaven.

In the aforesaid historical setting, we find the fascinating character of Enheduanna, who apart from working as the high priestess of the moon deity Nanna-Suen in Ur, also composed several works of literature, including two hymns to the Mesopotamian love goddess Inanna, worshipped as Ishtar, in Semitic religion.

She also wrote the myth of Inanna and Ebih and a collection of 42 temple hymns and through her written works, she changed the entire traditional culture, altered the nature of the Mesopotamian gods, along with the prevalent perception the people about the divine. Despite scribal traditions in the ancient world are often considered an area of male authority, contribution of Enheduanna in the rich literary history of Mesopotamia can never be ignored.

In her composition, The Exaltation of Inanna, Enheduanna described her struggle against an attempted coup by a Sumerian rebel named Lugal-Ane, who suspended her from the post as high priestess and forced into exile from the city.

She then found refuge in the city of Ĝirsu, where she composed the song Nin me šara, the performance of which was intended to persuade the goddess Inanna, as Ištar the patron goddess of her dynasty, to intervene to help her on behalf of the Akkadian empire. It is presumed that apparently, Inanna heard her prayer and through divine intercession, Enheduanna was finally reinstated to her rightful place in the temple.

While clearly asserting ownership over her creative works, Enheduanna also depicted the difficulties of the creative process in her hymns and commented about the challenge of describing divine wonders through the written words. However, her poetry has an artistically intelligent quality, which emphasises the superlative qualities of its divine muse, dedicated to the goddess of love. Her written praise of celestial deities has also been recognised in the field of modern astronomy and a crater on Mercury was named in her honour in 2015.

The works of Enheduanna were written in an ancient form of writing using clay tablets, known as cuneiform. Despite the lack of earlier sources has raised doubts about her authenticity as the author of myths and hymns and her status as a high rank religious official, the ancient records clearly identifies Enheduanna as the composer of those rich literary works.

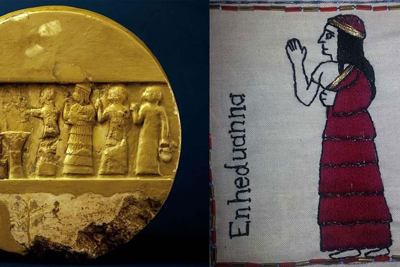

Aside from poetry, another important thing about her identification is the Disk of Enheduanna, discovered by the British archaeologist Sir Charles Leonard Woolley and his team of excavators at the Sumerian site of Ur in 1927. The recovered disk, shattered into several pieces and reconstructed subsequently, depicts the high priestess standing in worship in the centre of the image and wearing a cap and flounced garment, emphasizing the religious and social status of the priestess, along with her three male attendants. The other side of the disk contains inscriptions, depicting the identity of the four figures as Enheduanna, along with her Estate Manager, her hairdresser and her scribe. Two seals bearing her name, belonging to her servants and dating to the Sargonic period, have also been excavated at the Giparu at Ur. Nevertheless, Enheduanna is still remembered and honoured for her profound impact on ancient literature and culture and even today, poems are composed on the model that she created more than 4,000 years ago.