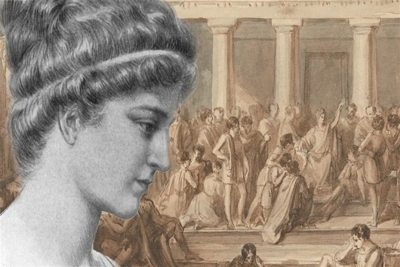

Hypatia, a philosopher, astronomer and mathematician of the ancient world, was born in a man’s world at the end of the 4th century, possibly in 370, although some scholars cite her birth as 350, in Alexandria, a part of the Roman Empire during that period. Renowned in her own lifetime as a great teacher and a wise counsellor, she was the daughter of the Greek scholar and mathematician Theon, the last Head Librarian of the Library of Alexandra, who refused to impose upon his daughter the traditional role assigned to women and raised her as one would have raised a son in the Greek tradition, by teaching her mathematics, astronomy and also philosophy.

However, nothing is known about Hypatia's mother, who is never mentioned in any of the extant sources.

While nobody is sure about the exact date of Hypatia’s birth, the suggested dates range from 350 to 370 AD. Many scholars agree with the view of the reputed German scholar Richard Hoche, who maintained that Hypatia was born around 370, since according to Damascius's lost work Life of Isidore, which preserved in the entry for Hypatia in the Suda, the large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, Hypatia flourished during the reign of Arcadius, the Roman Emperor from 383 to 408.

Hoche reasoned that, the description of Hypatia’s physical beauty in Damascius’s Life of Isidore implies that during that time, Hypatia was at most 30, and the year 370 was 30 years before to the half way of Arcadius's reign. In contrast, the theories that she was born as early as 350 are based on the wording of John Malalas, a Byzantine chronicler, who opined that Hypatia was old at the time of her death in 415. However, Robert Penella, Professor of Classics at Fordham University, New York, maintains that both theories are weakly based and that her birth date should be left unspecified.

Hypatia became a major academic force in Alexandria, by the time she turned 31. She has been credited with writing commentaries on the geometry of Apollonius of Perga’s treatise on conic sections and a commentary on Diophantus of Alexandria’s thirteen-volume Arithmetica. Many scholars of the modern age also believe that Hypatia may have edited the surviving text of Ptolemy’s Almagest, based on the title of her father’s commentary on Book III of the Almagest. She also worked on an astronomical table, which could be a revision of one of her father’s projects and her observations of the motion of the stars were explained in an original work entitled Astronomical Canon.

However, it is unfortunate that, all of her original work has been lost.

When she became an adult, Hypatia decided to remain unmarried and dedicate her life for science and teaching. Apart from that, to explain and make her students understand the scientific works, she wrote several notes, improving even the originals. The greatest achievement of Hypatia and her school in Alexandria was carrying the flame of philosophical inquiry into an increasingly darkening age. She believed and continued to spread the idea that mathematics was not at all a hard science based on proofs, but the sacred language of the universe. In her Platonist school in Alexandria, she taught her students that the cosmos is numerically ordered with the planets moving in orbits corresponding to musical intervals and creating harmonies in the space. Her students included the Christians as well as pagans and according to ancient sources, she was loved and appreciated for her method of teachings by the pagans and Christians alike. In addition to teaching her students, she also gave public lectures, which were attended by government officials seeking her advice on different matters and thus she established great influence with the political elite in Alexandria, earning rage and hatred of Cyril, the archbishop of Alexandria. She was popular and influential, but her increasing popularity inspired a fatal envy in the bishop. Apart from that, her sex irked her zealous Christian adversaries, who were dogged on restricting the influence of women in every sphere.

It was the time when the political situation of Alexandria was increasingly becoming complicated, as the Christians became desperate to make Alexandria a Christian city and started to burn the pagan temples. Under the prevailing circumstances, Orestes, the Roman prefect of Alexandria was in the midst of a political feud with Cyril, the archbishop of Alexandria, who was hostile to the non-Christian communities. It is presumed that, during that time Hypatia, who was in favour of her former student Orestes, advised him about the way to save the situation. Interestingly, Orestes loved Hypatia for her intelligence and beauty, but she turned down his advances, though they remained close. But their relationship ignited the spark and she became the scapegoat, as rumours spread wildly accusing her of preventing Orestes from reconciling with Cyril Unfortunately, despite her sharp intelligence, strong will, stamina and physical beauty, Hypatia could not save the situation for her.

On a early spring day in March 415 AD, Hypatia was brutally murdered by a mob of Christian men, called the Parabalani, a volunteer militia of monks serving as the henchmen to the archbishop, who had razed numbers of pagan temples, attacked the Jewish quarters, defiled masterpieces of ancient art and had already destroyed the remains of the Library of Alexandria for terrorizing the groups other than the Christians. The frenzied mob, led by a lector named Peter, forcibly pulled down the city’s beloved and respected teacher of mathematics and philosophy from her carriage on a street in Alexandria, dragged her to a church, stripped her naked and battered her to death. As if that was not enough, they tore her body into pieces and dragged her limbs through the town to a place called Cinarion, where the severed limbs were set on fire.

The brutal murder of Hypatia shocked the empire and transformed her into a martyr for philosophy. Even those Christian writers, who were hostile to her and claimed she was a witch, sympathetically recorded her death as a tragedy. Ridiculously, during the Middle Ages, Hypatia was co-opted as a symbol of Christian virtue and later, during the Age of Enlightenment, she became a symbol of opposition to Catholicism. In his 1853 novel Hypatia, Charles Kingsley, a priest of the Church of England, depicted her as the last of the Hellenes and in the 20th century, Hypatia became an iconic figure for women's rights and a predecessor to the feminist movement.