Located in the core of the Sahara, on the southwestern side of Libya, close to the Algerian border, the Tadrart Acacus is a sandstone massif range, known for its rock art that dates from 12,000 BC, reflecting the culture and natural changes in the area. The paintings, mostly located on the outer rocky walls or in the small shallow caves, are scattered throughout the mountain range, stretching for more than 250 km in the middle of an uninhabited wasteland. Together with the vast Tassili N’Ajjer plateau in southeast Algeria on the borders of Libya, it is the premier rock-art area in the world, with hundreds of engravings and thousands of paintings, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The incredible open-air gallery tells a story that traces the environmental effects of climate change on the people who have occupied the area over the millennia and according to the characteristics of the rock-art legacy, the gallery can be divided into distinct periods.

The oldest art in the area, which dates back from 10,000 to 6.000 BC and belongs to the so-called Wild Fauna Period, is characterised by the portrayal of animals that inhabited the area when it was much wetter than today and include elephants, giraffes, hippos and rhinos.

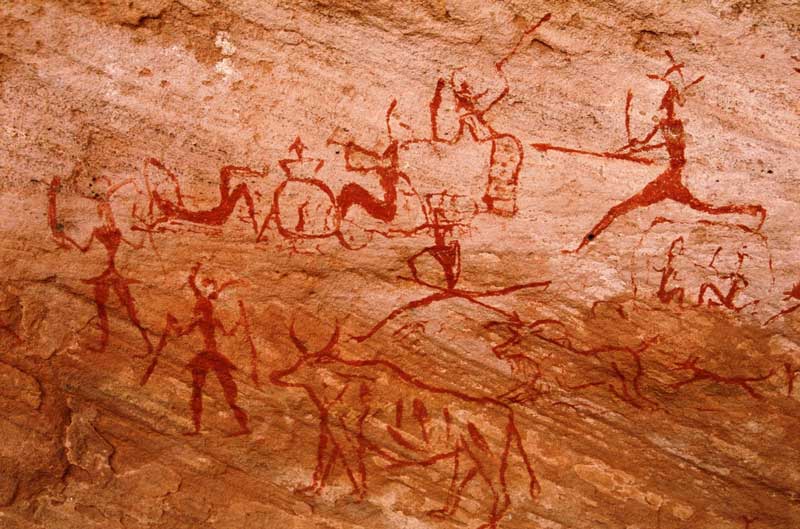

However, the Round Head Period, which prevailed from 8,000 to 6,000 BC, overlapped this era and human figures appear alongside painted circular heads, devoid of features, when people were living as hunter-gatherers. Nevertheless, the Round Head Period also gradually gave way to the Pastoral Period that prevailed between 5,500 and 2,000 BC, characterised by art depicting the introduction of domesticated cattle and a more settled existence with human figures, carrying spears and performing ceremonies. This was followed by the art of the Horse Period, during 1000 BC and AD 1, when the climate became progressively drier, long-distance travel became more important and horses and horse-drawn chariots were introduced in the cave art. Finally, the most recent period of rock-art in the Sahara, beginning from around 200 BC, is the Camel Period, as these animals have started to play an increasingly important role in the way of life of the people concerned.

Heinrich Barth was the first European, who found and reported about the Tadrart Acacus engravings in 1850 and later, the Frenchman Fourneau wrote about them, although he never visited the site.

Long after that, the Italian Royal Geographical Society carried out an expedition in 1930, to trace the cave paintings in the Tadrart Acacus, but for unknown reasons, its findings were not made public until 1940. However, after a full decade, a full expedition of the area was carried out by the Italian archaeologist Fabrizio Mori in 1950, whose accounts finally exposed the immense cultural value of the site.

Unfortunately, despite the rock art sites of Tadrart Acacus have survived for 14,000 years in the desert of southern Libya, today they are under serious threat. During the rule of Muammar Gaddafi from 1969 through 2011, the Department of Antiquities was almost neglected.

Moreover, the search for petroleum hidden underground since 2005 has placed rock art itself in danger. The Seismic hammers used to send shock waves below the ground for locating oil deposits had noticeable adverse effects on nearby rocks, including the ones that house the Tadrart Acacus rock art. Apart from that, vandalism reached a level of crisis, when graffiti was spray-painted across the surface of many of the paintings and people carved their initials into the rocks

Although following the murder of Gaddafi in 2012, efforts were made to train staff through a US$ 2.26 million UNESCO project, with the Libyan and Italian governments, UNESCO State of Conservation (SOC) reports from 2011, 2012 and 2013 indicate that not less than ten of the rock-art sites have been the object of deliberate and considerable destruction since at least April 2009.

However, in May 2013, UNESCO undertook a technical mission to build up a strategic plan to enforce the protection and management of the rock art at Tadrart Acacus. But it seems that the greatest threat to Libya’s diverse heritage is the trafficking of archaeological materials, for profit or to fund radical groups and until the fighting in Libya stops and archaeologists can effectively cooperate with the government and international organizations to restore and protect sites like the rock art at Tadrart Acacus, Libya’s rich trove of monuments and artefacts will continue to remain endangered.