In American History, Salem Witch Trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of more than 200 people accused of practising witchcraft, the devil’s magic, in the village of Salem in colonial Massachusetts, between February 1692 and May 1693. The Special Court, made up of magistrates and jurors and presided over by Chief Justice William Stoughton, sat in Salem in June of 1692 to hear the cases of witchcraft and the first to be tried was Bridget Bishop of Salem, accused of bewitching five young women. Her trial lasted eight days, officially starting the Salem Witchcraft Trials, in which she was found guilty and was hanged on 10 June 1692. Among thirty other people found guilty, fourteen women and five men from all stations of life followed her to the gallows on three successive hanging days, another man, named Gilles Corey, was pressed to death after refusing to enter a plea and at least five people died in jail, before the court was disbanded by Governor William Phipps in October of that year. Subsequently, the witchcraft court was replaced by the Superior Court of Judicature, which disallowed the spectral evidence, the belief in the power of the accused to use their invisible shapes or spectres to torture their victims, which had earlier sealed the fates of those tried by the Court of Oyer and Terminer. The new court also released those awaiting trial and pardoned those awaiting execution, signalling the end of the infamous Salem Witch Trials. However, the story did not end there and since the 17th century, the story of the trials has become synonymous with injustice and paranoia.

However, although the episode of the Salem Witch Trials is one of the most infamous incidents of mass hysteria in Colonial America, it was not unique. In the medieval and early modern eras, a section of people belonging to several religions, including Christianity, intentionally preached among the mass, for vested interest, the ludicrous idea that the devil could transfer their evil power to some people, known as witches, to harm others in return for their loyalty.

It created havoc and the absurd idea of witchcraft craze rippled through Europe from the 1300s to the end of the 1600s, when thousand of so called witches, mostly women, were cruelly executed. The European witch-hunt fervour peaked from the 1580s and 1590s to the 1630s, and 1640s and about three-fourths of those European witch hunts took place in western Germany, northern Italy, Francs, Switzerland and the Low countries, consisting of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. While the number of trials and the consequent executions varied according to time and place, it is generally believed that in total, around 110,000 persons were tried for alleged witchcraft, among which between 40,000 to 60,000 were executed.

Witches were believed to be the ardent followers of Satan, who had traded their souls for his assistance and they employ demons to accomplish their magical deeds, change their forms from human to animal or from one human to another and act as the familiar spirits of the victim. There is not much room for doubt that some individuals did worship the devil, but no one ever embodied the concept of a witch as previously described. Nevertheless, the process of identifying witches began with suspicions or rumours, although sometimes, rumours were spread with the intention to take revenge.

Generally, it was followed by accusations, leading to convictions and mostly executions. The Salem Witch Trials and the consequent executions were the results of a combination of church politics, family feuds and some hysterical children, all of which unfolded in a vacuum of political authority.

In the late 17th century, there were two parts of Salem consisting of a bustling commerce-oriented port community on Massachusetts Bay known as Salem Town and Salem Village, a smaller, poorer farming community of some 500 persons, located roughly 10 miles (16 km) inland from it. The village had two rival families, the well-heeled Porters, who had strong connections with Salem Town’s wealthy merchants, and the Putnams, who represented the less-prosperous farm families and sought greater autonomy for the village. Through the influence of the Putnams, Samuel Parris, a merchant from Boston by way of Barbados, became the pastor of the village’s Congregational church in 1689, who brought his wife, their three children, a niece and two slaves, a man named John Indian and a woman called Tituba, to Salem Village.

The relationship between the slaves and their ethnic origins are unknown, though it is believed that they were of African heritage and might be of Caribbean and Native American heritage.

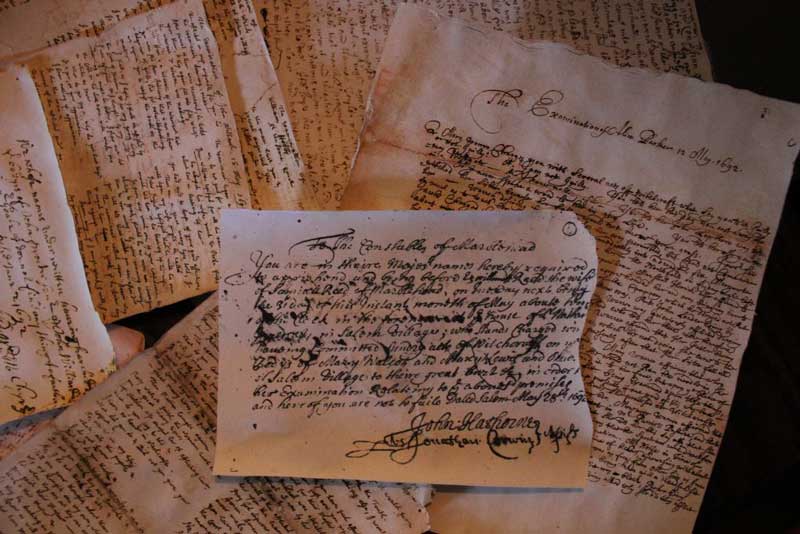

Samuel Parris quickly earned a bad name for his rigid ways and greedy nature. His orthodox preaching also divided the congregation and in the process, Salem was divided into pro-Parris and anti-Parris factions. But the villagers believed that the root of all their quarrelling was the work of the devil, which was evident to them because of the odd behaviour of the children of the pastor’s family. By that time, probably inspired by the voodoo tales told by Tituba, Parris’s daughter Betty, his niece Abigail Williams and their friend Ann Putnam Jr, began in fortune-telling and in January 1692, 9-year-old Betty and 11-year-old Abigail Williams, along with 12-year-old Ann started having fits. They screamed, threw things, uttered peculiar sounds, contorted their bodies into strange positions and complained of biting and pinching sensations. While their strange behaviour may have resulted from some combination of various diseases like epilepsy, encephalitis, delusional psychosis or convulsive ergotism due to food poisoning, the local doctor, William Griggs, put the blame on the supernatural. Finally, on 29 February, under pressure from magistrates Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne, the colonial officials, Betty and Abigail claimed to have been bewitched by three women, namely Tituba, the Caribbean woman enslaved by the Parris family; Sarah Good, a homeless beggar and Sarah Osborne, an elderly woman who was once scorned for her romantic involvement with an indentured servant. Starting from 1 March 1692, the local magistrates conduct a public inquiry and interrogated all the three women, when Good and Osborne strongly claimed their innocence. Initially, Tituba also claimed to be blameless, but after being repeatedly badgered, she told the magistrates what they apparently wanted to hear, probably out of fear for her vulnerable status as a slave. In three days of vivid testimony, she confessed that she had been visited by the devil and made a deal with him. She vividly described the images of black dogs, red cats, yellow birds and a tall man with white hair, who wanted her to sign his book. She admitted that she had signed the book, in which she saw the names of Sarah Good and Sarah Osborn, along with seven others that she could not read.

The confession of Tituba opened the floodgate of witch hunting, as the magistrates accepted it as evidence of the presence of more witches in the community and a stream of accusations followed over the next few months. Significantly, the newly suspected witches were not just outsiders and outcasts, but rather upstanding members of the community like Rebecca Nurse, a mature woman of some prominence, and Martha Corey, a loyal member of the church in Salem Village, very much concerned about the community. As the weeks passed, many of the accused proved to be enemies of the Putnams, while the Putnam family members and in-laws would end up being the accusers in dozens of cases. The questioning got more serious in April, when dozens of people from Salem and other Massachusetts villages were brought in for questioning, in the presence of the colony’s deputy governor, Thomas Danforth and his assistants. On 27 May 1692, by order of Sir William Phipps, the governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, a Special Court of Oyer and Terminer was formed, consisting of seven judges and presided over by William Stoughton, the colony’s lieutenant governor, to hear and decide, but at the end, the accused were forced to defend themselves without the aid of counsel. However, those who confessed and named other witches were spared the court’s vengeance, since the Puritans believed that they would receive their punishment from God, but those who insisted upon their innocence met harsher fates and became martyrs to their own sense of justice. On the 2nd day of June, Bridget Bishop, an older woman known for her gossipy habits and promiscuity, who had been accused and found innocent of witchery some 12 years earlier, was brought in front of the special court and despite her claim to be as innocent as the child unborn, she became the first person hanged on 10 June, on Gallows Hill in Salem Village. On July 19, five more convicted persons were hanged, including Rebecca Nurse and Sarah Good. Even, George Burroughs, one of the ex-ministers in Salem Village from 1680 to 1683, was summoned, accused of being the witches’ ringleader, convicted and hanged on 19 August, along with four others. Eight more convicted persons were hanged on September 22, which included Martha Corey, while her old husband was pressed beneath heavy stones for two days until he died, as he refused to submit himself to a trial.

However, on 29 October 1692, when the accusations of witchcraft extended to include his wife, Governor Sir William Phipps stepped in, ordering a halt to the proceedings of the Special Court of Oyer and Terminer and replacing it with a Superior Court of Judicature. After that, within May 1693, Phipps also pardoned all those imprisoned on witchcraft charges. But by that time, the damage was already done. Although the State of Massachusetts formally apologized for the trials in 1957, it was not until 2002 that the last 11 of the convicted were fully exonerated.