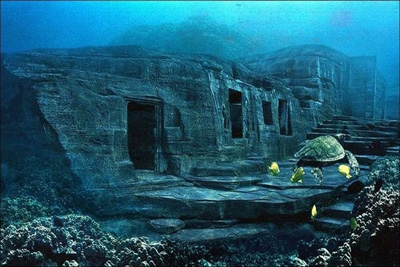

Submerged in the depth of around 82 feet (25 m) near the coast of the Japanese island of Yonaguni, about a hundred km east of Taiwan, lie a series of intriguing and massive rock formations that have mystified scholars since their discovery in 1987. The strangely symmetrical shapes and structures, known as the Yonaguni Monument, and speculated to have existed more than 10,000 years, is an enigma for the scholars as nobody is sure whether the formation is from natural causes, or completely man-made, or had been altered by man. The strange 164 feet (50 m) long and 65 feet (20 m) wide enormous Yonaguni Monument, one of the most unusual underwater sites of the world, resembling an architectural complex, includes structures like the Inca pyramids, flat terraces, and almost perfectly carved massive steps with straight edges.

During the winter season, the sea off Yonaguni becomes a popular diving location for its large population of hammerhead sharks. While searching for a good spot to observe those sharks, Kihachiro Aratake, a director of the Yonaguni-Cho Tourism Association, first noticed the strange singular seabed formations in 1986.

Shortly after the discovery, a group of scientists under the leadership of Masaaki Kimura, a marine geologist at the University of the Ryukyu, visited the site and explored the monument for nearly two decades.

Kimura was convinced that the site was carved thousands of years ago, when the landmass was above water, in other words, when the sea level was around 130 feet (40 m) lower than the present level. He maintained that the Yonaguni’s numerous right angles, strategically placed holes, and aesthetic triangles are signs of human alteration. He believed that the carvings on the monument resemble Kaida script, a type of ancient pictographic glyphs, which were once used in the Yaeyama islands and the island of Yonaguni, both of which are today part of Japan. According to Kimura, the stepped pyramid, castles, roads, and even a stadium can be easily identified within the complex, and it is probably the remains of the Lost Continent of Mu, located in the Pacific Ocean, and comprised of most of the small islands in the mid-Pacific, including Guam, Fiji, Christmas Island, Midway, and Hawaii. Probably, it was washed away in the late 1700s, during which a tsunami ravaged the island of Yonaguni with 130 feet of waves.

Exponents of the theory, who believe that the Yonaguni Monument was man-made, produced numerous photographs showing the obvious resemblance of the underwater terraces of the site with the tall mountain temple complexes in South America, especially those which were carved in the rocks of the Peruvian Andes.

They argue that in all probability, the massive complex was submerged due to a natural cataclysm like a devastating earthquake or tsunami. However, that possibility is not unlikely as Japan and the surrounding region are extremely seismic, powerful earthquakes and tsunamis occur every decade, especially a terrible tsunami created havoc in the region around the end of the 17th century.

Although nicknamed Japan’s Atlantis, some scholars maintain that the Yonaguni Monument reasonably resembles the natural formations found in many other places around the world with defined edges and flat surfaces. The Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland is an example of such a formation where thousands of interlocking basalt columns were created by massive volcanic eruption millions of years ago. Despite the arched entrances, narrow passageways, tactically created holes, and parallel ninety-degree angles, the remarkable formations of the Yonaguni Monument are generally believed to be natural as the structure is attached to a larger rock mass as opposed to being assembled out of freestanding rocks.

It is composed of medium to very fine sandstones and mudstones, and the well-defined layers of the site are likely to have gradually formed about 20 million years ago due to its location in an earthquake-prone region. In support of the view, Robert Schoch, a professor of science and mathematics at the Boston University opined that sandstones tend to break along the plane and creates straight edges, especially in an area of intense tectonic activity with lots of faults.

Nonetheless, despite the confusion and contradictions about the origin of the Yonaguni Monument, neither the Agency for Cultural Affairs of the Japanese government nor the Government of Okinawa Prefecture recognized the submerged formations off Yonaguni as a heritage or cultural site. Even no action has been taken so far to carry out research work or protect the site from mishandling. However, the formation has since become a relatively popular attraction for divers to observe the hammerhead sharks, with the added attraction of the unusual submerged formations, despite the strong oceanic currents prevalent in the area.