Born as Maria Krystyna Janina Skarbek, in or near Warsaw in Poland on 1 May 1908, the daughter of a wealthy assimilated Jewish family, subsequently became famous as Christine Ganville. With the support of her father, she took a liking for riding horses, which she sat astride, unusual for a girl and also became an expert skier during visits to Zakopane in the Tatra Mountains of southern Poland. Due to straitened financial condition, the family had to give up their country estate and moved to Warsaw in 1920. Armed with her stunning look, Skarbek entered the Miss Polonia contest, an early beauty pageant, in 1930. Unfortunately, she lost her father during the same year and had to take a job at a Fiat car dealership, but soon became ill from automobile fumes and had to give up the job. She received compensation from her employer's insurance company and according to the advice of the physician to lead as much of an open-air life as possible, she began spending a great deal of time hiking and skiing the Tatra Mountains.

In the same year, on 21 April, she married a young businessman, Gustaw Gettlich and as they proved incompatible, the marriage soon ended in divorce. A subsequent love affair became futile, as the mother of the lover refused to consider the penniless divorcée as a potential daughter-in-law. On 2 November 1938 she married Jerzy Gizycki, who saved her on a Zakopane ski slope, when she lost control and he stepped into her path and stopped her descent. Soon after the marriage, Jerzy Gizycki accepted a diplomatic posting to Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, where he served as the Consul General of Poland, until September 1939, when Germay invaded Poland.

The pair sailed for London, where Skarbek sought to offer her services in the struggle against the common enemy. Initially, the British authorities showed little interest in her proposal, as she was a woman. However, eventually they were convinced by Skarbek's acquaintances, especially as she was introduced to the Secret Intelligence Service, by an eminent journalist, Frederick Augustus Voigt. She was enrolled in what was then known as Section D, which later became the Special Operations Executive and undertook espionage, reconnaissance and sabotage missions in occupied territory. The emerging spy, Krystyna Skarbek, was given the cover name Christine Granville. After the war, she adopted the name permanently throughout her life.

As positive news about the fight against Hitler was vital to fuel the resistance, Christine proposed to ski into Nazi-occupied Poland and deliver British propaganda. After some initial hesitancy the British Special Operations Executive approved the plan and on her first mission, she was sent to a place between the then neutral Hungary and occupied Poland, to prove her stamina and courage as an intelligence courier. She convinced the Olympic skier Jan Marusarz to escort her across the snow-covered Tatra Mountains into Nazi-occupied Poland and departed for Budapest on 21 December 1939. It was the coldest winter in memory and it was tough skiing by night to dodge border patrols in temperatures of - 30 Celsius.

Arriving in Warsaw, she pleaded vainly with her mother to leave Poland immediately, which she refused and soon died at the hands of the occupying Germans in the Pawiak prison in Warsaw. Nevertheless, Skarbek's intelligence activities in Warsaw were successful enough and working with the spies for the Polish resistance, she assembled a dossier with photos of the German troops massing on the borders of the Soviet Union, though the two countries had signed a nonaggression pact.

In Budapest Skarbek met a Polish army officer, Andrzej Kowerski, whom she met before as a child. In a pre-war hunting accident, Kowerski had partly lost one of his legs and currently was exfiltrating Polish and other Allied military personnel and collecting intelligence as Andrew Kennedy. Skarbek, working together with Kowerski, organised sharp vigilance of all the rail, road and river traffic near the borders with Romania and Germany. She also sabotaged the main communications on the River Danube, as well as provided vital intelligence on oil transports to Germany from Romania's Ploiesti oil fields. However, both of them were arrested early in 1941 and interrogated by the German secret police, the Gestapo and faced torture and death if they were proved to be enemy agents. During her interrogation, Skarbek intentionally bit her own tongue hard enough to draw blood, coughed hard, and succeeded in convincing a Hungarian doctor that both of them were sick and suffering from tuberculosis. The terrified Gestapo officers released both of them to avoid the devastating disease. After the incident, Skarbek was smuggled out of Hungary in the trunk of a Chrysler car belonging to British ambassador Sir Owen O'Malley, crossing successfully into Yugoslavia. Later, O'Malley remarked that Skarbek was the bravest person he ever knew and she could do anything with a dynamite, except eat it. Kowerski, who had been working in Hungary under the cover of a used car dealer, followed her in an Opel, which he claimed to have sold to someone across the border. After that, the two made their way through hundreds of miles of Nazi-occupied territory to SOE headquarters in Cairo, Egypt.

On their arrival in Cairo they were shocked to learn that they were under suspicion as they passed through Syria, which was at the time under the control of the Vichy government in France, considered as a puppet of the Nazi Germany. The British assumed that they could not have arranged for a transit visa to make the trip, unless they were double agents. However, after a considerable period of investigation, Skarbek was cleared, partly because her prediction that Germany would invade the Soviet Union came true on 22 June 1941. Eventually, Kowerski could also cleared up the misunderstandings and was able to resume intelligence work.

In July of 1944, Krystyna Skarbek, code-named Pauline Armand, parachuted into southern France, with the mission to assist the French resistance fighters, before the commencement of the American ground invasion of southern France at the end of the summer. Within a short time, she became legendary among the British intelligence agents. On one occasion, she was stopped near the Italian border by two German soldiers, who ordered to put her hands in the air. She did so, revealing a grenade under each arm with the pins withdrawn. As she calmly threatened the soldiers to drop the grenades, killing them all, the scared Germans fled immediately. On another occasion she dived into a thicket to evade a German patrol, only to find herself face to face with a large Alsatian hound. Somehow she managed to make the dog quiet while making noises, which suggested the Germans that they themselves were about to be ambushed. She promptly took advantage of the ensuing confusion and escaped another close call. However, her most celebrated exploit was the rescue of the Resistance leader Francis Cammaerts, who was imprisoned by the Gestapo on 13 August 1944.

Krystyna Skarbek, a trained combatant, was deadly with her pistol. However, she preferred silent killing with her knife or even bare hands. She always kept a knife strapped to her thigh, so that she was ready for action at any time. She was bold and intrepid and a daring parachuter. On 6 July 1944, she parachuted into southeastern France to become a part of the ’Jockey’ network, directed by a Belgian-British lapsed pacifist Francis Cammaerts. She assisted the group by linking the Italian partisans and the French Maquis, for joint operations against the Germans in the Alps. In August 1944, as the Allies invaded southern France in Operation Dragon, the Jockey circuit kept open the route from Cannes to Grenoble, allowing the Allied armies to get clear of the lower Rhône valley.

Unfortunately, on 13 August 1944, two days before the Allied Operation Dragoon landings in southern France, Francis Cammaerts, along with SOE (Special Operations Executive) agent Xan Fielding and a French officer, Christian Sorensen, were arrested at a roadblock by the Gestapo in Digne-les-Bains, or simply and historically Digne, when a vigilant guard casually searched their belongings at a checkpoint and found that their banknotes had consecutive serial numbers, which blew apart the cover story that they did not know each other. Probably, the Gestapo did not have the slightest idea about whom they arrested. However, it made little or no difference, since the order of the day was to execute anybody held as a suspected enemy agent, without any trial.

By that time, Krystyn had risen to be the second-in-command to Francis Cammaerts, a rising star in the SOE who was in charge of British liaison with resistance cells in the area. However, she was a passionate woman by nature, had many lovers in the past and had also fallen for Cammaerts as they fought the Nazis together. A confidential report filed by her and hidden away for years revealed how all the efforts of the Resistance could have come to nothing, if she did not take an unusually defiant rescue attempt and saved her almost executed lover.

As the news of the arrest was known, Krystyn tried to convince and begged the local Resistance members to mount a rescue attempt to bust their men out of prison by force. However, as that was considered as a suicide mission, the leaders rejected her proposal. Nevertheless, Krystyn did not give up, resolved to save the men and hatched an incredibly reckless plan. She started her mission alone, by skulking around the prison and singing a popular American blues ballad, until she heard Cammaerts sing it back. As she became sure about the spot, she entered the prison and told the guards that she was related to a senior British diplomat and therefore somebody with tremendous political power. She demanded that she be allowed to negotiate the release of the British agents. She repeated it to the captain of the guards and warned him about the imminent Allied invasion. She also said that the nearby town of Digne was a prime target which would be bombed, a claim she later described as 'a stab in the dark'. She warned the officer that he was in danger of a horribly painful death at the hands of the French mob when the Allies came, as they knew he was the head of the Gestapo in the area and the only way to save his own skin was to free the prisoners to earn himself a pardon. All through the long conversation, the Gestapo officer kept his gun fixed on Krystyn, but was finally won over by her mixture of charm and brazen lies. She secured an agreement that the prisoners would be freed in exchange for a ransom of two million francs, which would be dropped by the SOE within 24 hours by parachute. As Cammaerts and two other British prisoners were awakened and herded toward a car, they were convinced that they were about to be executed. However, they found, Krystyn was waiting for them in the car.

Several years after the incident, while she was in London, she told another Pole and fellow WW II veteran that, during her negotiations with the Gestapo, she had been unaware of any danger to herself. However, after their escape, she realized what she did and that the Gestapo officer could even shot her at any moment.

Krystyna Skarbek was one of the few SOE female field agents promoted beyond a junior officer to the rank of a Captain. She was awarded the British George Medal and the French Croix de Guerre, both high military honors and was appointed to the Order of the British Empire (OBE), an award normally associated with officers of the equivalent military rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

However, after the end of the War, Krystyn Skarbek found it difficult to adapt to civilian life. She was left without financial reserves or a native country to return. She applied for British citizenship, but the processing of her application was delayed due to her murky past. Though she ultimately convinced the British authorities to grant her British citizenship, she was left almost destitute. As her five months' of severance half-salary from the SOE ran out, she had to work as a hotel housekeeper, switchboard operator, and a salesgirl at Harrods department store.She applied for a job at the British United Nations mission in Geneva, which was turned down as she was not British. Gradually, things went from bad to worse for her. She became depressed and suffered from the injuries sustained when she was hit by a car. In desperation to survive, she took the job of a stewardess on the ocean liner ‘Rauhine’, in 1951. Following the order of the captain of the ship, the crew members were to wear their wartime decorations. However, Skarbek's splendid George Medal earned resentment from her English-born colleagues, as none of them believed that she had really earned every one of the chest full that she displayed. The only member of the crew, who believed she her, was a fellow steward, a man named Dennis Muldowney, with whom she had a relationship. Ultimately, the relationship failed, as she rejected him. However, Dennis Muldowney could not accept her rejection, became obsessed with her and began to monitor her movements. On 15 June 1952, while packing for a trip to visit Kowerski, the brave lady was suddenly stabbed to death in the Shelbourne Hotel, in London. Her assailant was Dennis George Muldowney, who pleaded guilty and was hanged on 30 September 1952.

Krystyn Skarbek was interred in St Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery,northwest London. Following the death of Andrzej Kowerski in December 1988, his ashes were flown to London and interred at the foot of Skarbek's grave. The grave was renovated by the Polish Heritage Society in 2013.

Long after her horrific death, when the Shelbourne Hotel was bought by a Polish group in 1971, they found Krystyn’s trunk in a storeroom, which contained her clothes, papers, and the dagger issued by the SOE. The dagger, her medals, and some of her papers are now displayed in the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum in Kensington, London

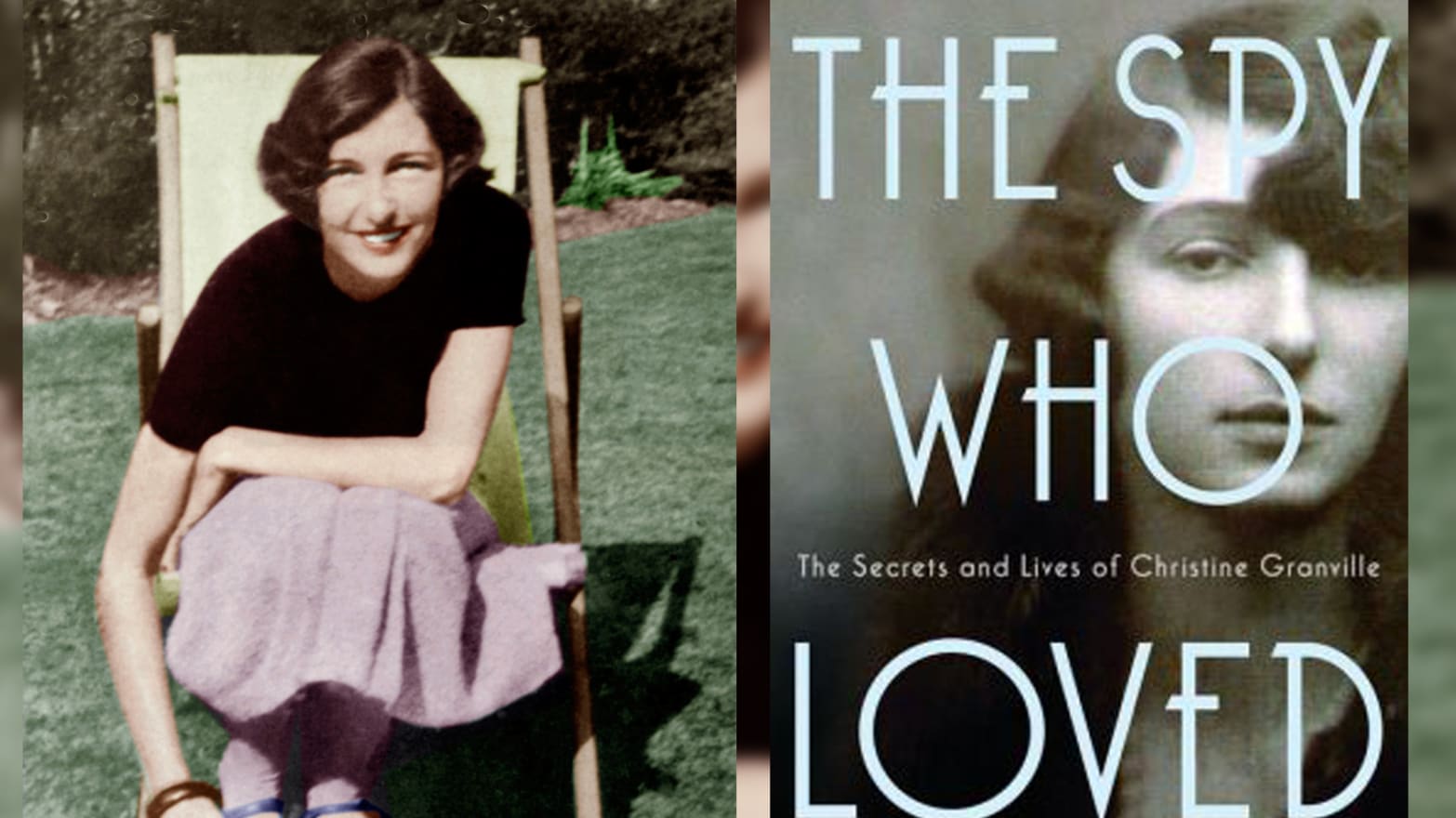

The biography of the amazing woman named Krystyn Skarbek, who became famous as Christine Granville, was penned by Clare Mulley and published in 2013 under the title, The Spy Who Loved: The Secrets and Lives of Christine Granville.The film rights of the book have been sold and rumours are that Angelina Jolie is interested in picking this up as a project. It is also rumoured that Winston Churchill’s daughter Sarah was pitched to play Krystyna in the movie, who reportedly said that Krystyna was her father’s favourite spy.

Renowned artist Ian Wolter, husband of the biographer Clare Mulley, created a bust of Skarbek, using soil from Poland and soil from a park in London, which was used to train Polish agents during WWII. The bust was placed at the Polish Hearth Club in London, where she used to recount the stories of her exploits during the war with fellow Polish refugees.

It has been popularly said that in his first James Bond novel Casino Royale, the author Ian Fleming modeled Vesper Lyndon on Christine Granville. However, her biographer Clare Mulley objected the view, when she wrote, Fleming is more likely to have been inspired by the stories he heard than the woman in person. In fact, Fleming never claimed to have met her.